- TOP

- Search Criteria

- Four Differences Between Japanese Temples and Shrines

STORY

The More You know: Four Differences Between Japanese Temples and Shrines

Japan is home to countless shrines and temples. In just the city of Kyoto alone the estimated combined total for temples and shrines was 5,570 as of 2015 according to a survey conducted by Kyoto Prefecture.

What's more, Shinto and Buddhism are syncretized in Japan; therefore it's not uncommon to find temples inside shrines and visa versa. So how can you tell a shrine from a temple? While there are exceptions to every rule, below are four ways in which temples and shrines typically differ from each other.

Jinja (神社) is the Japanese word for a Shinto shrine and otera (お寺) the one indicating a Buddhist temple. As such, names like Yasaka-jinja literally mean Yasaka Shrine. Taisha (大社) is also used to mean "grand shrine" as in Fushimi Inari Taisha. Lastly, jingu (神宮) is also used as in Meiji-jingu.

The pronunciation for temple changes a bit once it moves around to the end of the temple’s name. In some cases, the pronunciation changes to dera as in Kiyomizu-dera. In others, it becomes ji as in Kinkaku-ji. Lastly, in (院) also indicates a temple as we see with Byodo-in.

Torii

Along with Mt. Fuji, geisha, and perhaps sushi, the torii (鳥居) of shrines have become a symbol of Japan abroad. You often see these along the sando (参道), or the path leading up to a shrine. However, the familiar vermilion gates made of wood known as myojin torii (明神鳥居) are actually just one of more than fifteen styles that differ in areas like shape, material, and color.

Sanmon

One of the gates of a Buddhist temple is called the sanmon (三門). Depending on the temple, san may be written using the kanji for mountain (山) or the one for the number three (三). The first way comes from the fact that temples (and consequently their gates) were once typically built in the mountains.

The second reading comes from the fact that the gate has three entrances. Each one is thought to represent one of the three aspects of Buddhist training needed to attain enlightenment: emptiness (mu; 空), formlessness (muso; 無相), no-action (musaku; 無作). For this reason, the sanmon may also be called the sangedatsumon (三解脱門), or the gate of the three liberations.

Komainu

You’ll often find a pair of komainu (狛犬) lion-dogs between the torii and the haiden (拝殿) or front shrine. It’s the job of these mythical protector-beasts to drive away demons.

One komainu has its mouth open and the other has it shut. This represents the concept of the beginning and the end of all things or the universe. This concept is often expressed as alpha and omega in western cultures. In Japanese, this concept is called aun (阿吽). The open-mouthed komainu is a; the closed is un. Some shrines like Fushimi Inari may have foxes in place of komainu while others may have mice.

Nio

Known collectively as nio (仁王) or kongourikishi (金剛力士), many temples have a pair of these fearsome-looking deities sitting on either side of the gate to keep out distrustful enemies. Like their komainu counterparts, these statues are also often depicted in a mouth-open, mouth-closed pair to represent aun.

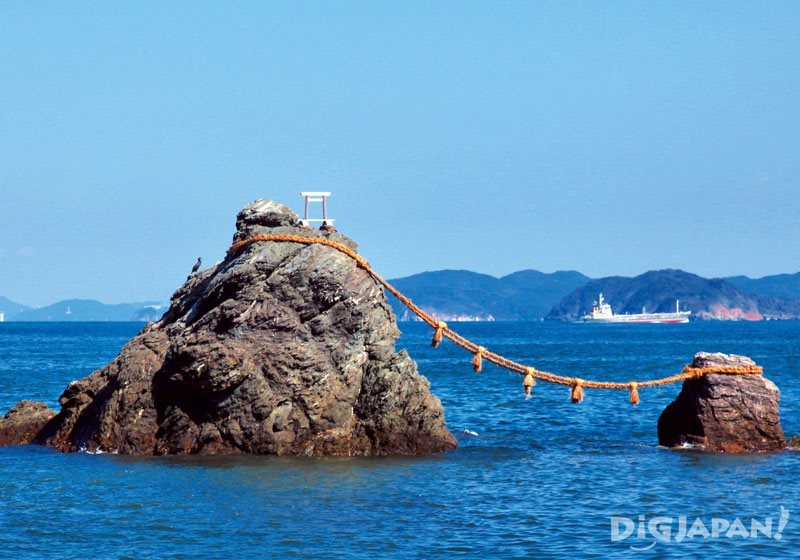

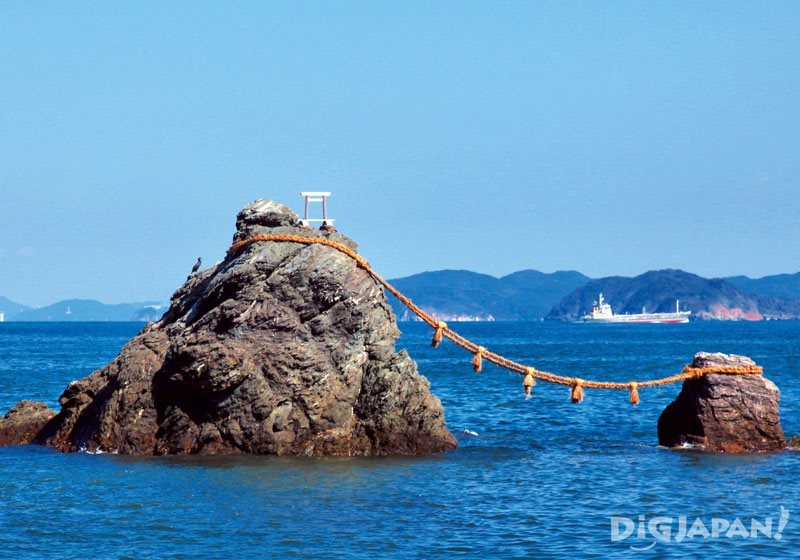

Meoto Iwa at Futami Okitama-jinja in Mie Prefecture.

Meoto Iwa at Futami Okitama-jinja in Mie Prefecture.

Nature, mirrors, etc.

In Shinto, it is thought that kami or gods reside in all things. Furthermore, objects like mountains, forests, impressive trees, unusual rocks, and other objects and places in nature are thought to have especially strong spiritual qualities and become objects of worship. This is sometimes indicated by a thick rope called a shimenawa (標縄).

Mirrors may also be objects of worship. In particular, there is said to be a sacred mirror called Yata no Kagami (八咫鏡), one of the three sacred treasures of Japan (sanshu no jingi; 三種の神器), enshrined at Ise Jingu Shrine in Mie Prefecture.

The principal object of worship or meditation at a temple is usually the butsuzo or image of the Buddha. The exact depiction depends on factors such as the particular sect of Buddhism represented at the temple as well as the historical time in which the image was created. These images may take the form of carved wooden statues, but some temples display pictures instead.

While there are many variations among temples and shrines given the sheer number of them that exist, these four points are a good starting place for learning more about them. If you found this article helpful, be sure to share on Facebook and Twitter!

What's more, Shinto and Buddhism are syncretized in Japan; therefore it's not uncommon to find temples inside shrines and visa versa. So how can you tell a shrine from a temple? While there are exceptions to every rule, below are four ways in which temples and shrines typically differ from each other.

Nomenclature

Yasaka-jinja in Kyoto.

Jinja (神社) is the Japanese word for a Shinto shrine and otera (お寺) the one indicating a Buddhist temple. As such, names like Yasaka-jinja literally mean Yasaka Shrine. Taisha (大社) is also used to mean "grand shrine" as in Fushimi Inari Taisha. Lastly, jingu (神宮) is also used as in Meiji-jingu.

Kinkaku-ji in Kyoto.

The pronunciation for temple changes a bit once it moves around to the end of the temple’s name. In some cases, the pronunciation changes to dera as in Kiyomizu-dera. In others, it becomes ji as in Kinkaku-ji. Lastly, in (院) also indicates a temple as we see with Byodo-in.

The Gates

The torii at Heian-jingu in Kyoto.

Torii

Along with Mt. Fuji, geisha, and perhaps sushi, the torii (鳥居) of shrines have become a symbol of Japan abroad. You often see these along the sando (参道), or the path leading up to a shrine. However, the familiar vermilion gates made of wood known as myojin torii (明神鳥居) are actually just one of more than fifteen styles that differ in areas like shape, material, and color.

The Sanmon at Chion-in in Kyoto.

Sanmon

One of the gates of a Buddhist temple is called the sanmon (三門). Depending on the temple, san may be written using the kanji for mountain (山) or the one for the number three (三). The first way comes from the fact that temples (and consequently their gates) were once typically built in the mountains.

The second reading comes from the fact that the gate has three entrances. Each one is thought to represent one of the three aspects of Buddhist training needed to attain enlightenment: emptiness (mu; 空), formlessness (muso; 無相), no-action (musaku; 無作). For this reason, the sanmon may also be called the sangedatsumon (三解脱門), or the gate of the three liberations.

The Guardians

Komainu at Ujigami-jinja in Kyoto.

Komainu

You’ll often find a pair of komainu (狛犬) lion-dogs between the torii and the haiden (拝殿) or front shrine. It’s the job of these mythical protector-beasts to drive away demons.

One komainu has its mouth open and the other has it shut. This represents the concept of the beginning and the end of all things or the universe. This concept is often expressed as alpha and omega in western cultures. In Japanese, this concept is called aun (阿吽). The open-mouthed komainu is a; the closed is un. Some shrines like Fushimi Inari may have foxes in place of komainu while others may have mice.

A kongourishiki at Ninna-ji in Kyoto.

Nio

Known collectively as nio (仁王) or kongourikishi (金剛力士), many temples have a pair of these fearsome-looking deities sitting on either side of the gate to keep out distrustful enemies. Like their komainu counterparts, these statues are also often depicted in a mouth-open, mouth-closed pair to represent aun.

Objects of Worship

Meoto Iwa at Futami Okitama-jinja in Mie Prefecture.

Meoto Iwa at Futami Okitama-jinja in Mie Prefecture. Nature, mirrors, etc.

In Shinto, it is thought that kami or gods reside in all things. Furthermore, objects like mountains, forests, impressive trees, unusual rocks, and other objects and places in nature are thought to have especially strong spiritual qualities and become objects of worship. This is sometimes indicated by a thick rope called a shimenawa (標縄).

Mirrors may also be objects of worship. In particular, there is said to be a sacred mirror called Yata no Kagami (八咫鏡), one of the three sacred treasures of Japan (sanshu no jingi; 三種の神器), enshrined at Ise Jingu Shrine in Mie Prefecture.

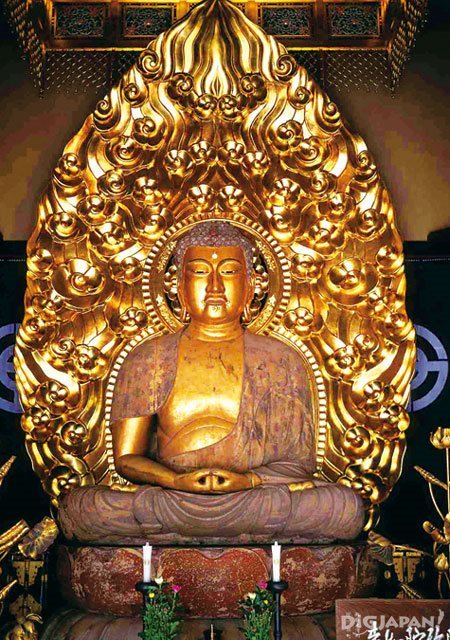

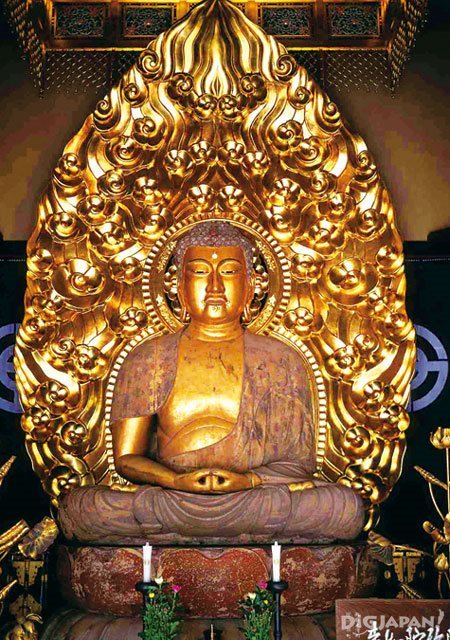

The Butsuzo at Hasedera in Kamakura.

ButsuzoThe principal object of worship or meditation at a temple is usually the butsuzo or image of the Buddha. The exact depiction depends on factors such as the particular sect of Buddhism represented at the temple as well as the historical time in which the image was created. These images may take the form of carved wooden statues, but some temples display pictures instead.

While there are many variations among temples and shrines given the sheer number of them that exist, these four points are a good starting place for learning more about them. If you found this article helpful, be sure to share on Facebook and Twitter!

Liked this story? Like DiGJAPAN!

on Facebook for daily updates!

THIS ARTICLE IS BASED ON INFORMATION FROM 07 25,2016 Author:Rachael Ragalye

NEW COMMENT | 0 COMMENTS

Open a DiGJAPAN!

account to comment.

Open a DiGJAPAN! Account