- TOP

- Search Criteria

- Osechi—the New Year’s Cuisine with Ingredients Said to Attract Good Luck

STORY

Osechi—the New Year’s Cuisine with Ingredients Said to Attract Good Luck

by SHUN GATE

Originally published December 2016

The main food associated with Japan’s New Year is none other than osechi cuisine.

The number of stacked boxes the food comes in, how it is presented and what items it comprises of may have changed with time, but the image of a Japanese family surrounding a table full of osechi, wishing for happiness in the coming year, has not.

To understand more about Japan’s New Year cuisine, we visited Takako Tsubuku, Managing Director of the Ajinomoto Foundation for Dietary Culture, a public interest incorporated foundation.

The surprising origin of osechi, born from the Japanese New Year

From the large volumes of books housed in the Ajinomoto Foundation for Dietary Culture, Tsubuku showed us a book by Ayao Okumura, a leading researcher of Japan’s traditional cuisine, titled What is Japanese cuisine?

Tsubuku says that this book mentions the surprising origin of osechi, which Okumura figured out from his research on ancient manuscripts.

According to Okumura, the main dish eaten during Japan’s New Year used to be zoni, which is cooked rice cakes in soup with vegetables; osechi was originally a simple assortment of several dishes that accompanied the zoni, which was the main dish.

Like obon in mid-August, Japanese people used to believe that their deceased ancestors came back to their homes in the New Year as well, this time as “gods of the year.” Families shared the rice cakes and vegetables that were offered to the gods in the New Year, which marked the beginning of zoni. As time passed and a larger variety of ingredients became available, people from samurai and rich merchant households started to prepare food in large stacked boxes.

Also, the custom of cooking food on New Year’s Eve, saving it for the New Year, takes after the Chinese Cold Food Festival, which takes place around the New Year. In China, people avoided lighting a fire in their furnaces during the New Year because Taoism taught them that the god of furnaces visited them in the New Year.

In Japan, it is said that people also started cooking food for the three first days of the year on New Year’s Eve and put the food in stacked boxes, to avoid tainting the “holy fire” needed to cook the zoni shared by the gods and people over the New Year.

As such, osechi started to spread among the people from around 1700 as a cuisine to welcome the gods in the New Year.

The word osechi is also said to have come from sechie, seasonal feasts held in the New Year and other festive seasons that the emperor and his vassals would have. This tradition started in the Nara period (710 to 764). The book states that in the late Edo period (1603 to 1868), people started calling the New Year feast osechi.

Osechi, the cuisine that changes with time

After the Meiji period (1868 to 1912), the dietary lifestyle of Japanese people changed significantly and they started to use chicken broth and meat when making zoni. Similarly, items served in stacked boxes became more luxurious and osechi began to secure its place as the main food of the Japanese New Year (at this stage, the cuisine itself was not called osechi yet).

The menu of a cooking class held by a Kappo (traditional Japanese) cuisine chef in the Taisho period (1912 to 1926) Tokyo shows datemaki (egg rolls), kamaboko (fish cake) and kinton (mashed chestnuts) for the first time in recorded media. There are also records that the Osaka Mitsukoshi Department Store sold sets of filled osechi boxes. Later in the Showa period (1926 to 1989), ham and roast beef made their way into the menu, creating eclectic Japanese-Western style stacked boxes.

“The Ajinomoto Foundation for Dietary Culture has back issues of the cooking magazine ‘NHK Kyouno Ryouri (Cooking Today)’. If you look at the New Year’s issues from ten, twenty years ago, you can see that osechi has changed from generation to generation—going through them is fun. You can see that they were influenced by Western hors d’oeuvres, too. There has been a growing emphasis on beautiful color coordination. Osechi will probably continue to evolve,” says Tsubuku.

Osechi changes with time. But the practice of families’ wishing for each others’ happiness and eating lucky foods at the beginning of the year, the heart of this cuisine, will probably never change.

Enclosing the wish for unchanging happiness

What does each food item in osechi cuisine symbolize? We asked Tsubuku to explain the nine representative osechi foods.

Top left:: Pounded burdock root

Burdock roots are cooked until soft, pounded and then slit open. In some areas it was called “open burdock” and was thought to be a dish that would “open up” good luck. Burdock root was also believed to remove “bad” blood and had been a good luck food long before it became a member of osechi cuisine. Also, as burdock grows long, fine roots in the ground, it also entails the wish for the household to remain safe and prosperous.

Top center: Kazunoko

Kazunoko is herring roe. Herring is called nishin in Japanese, and is also a homophone for “two parents.” As such, people use kazunoko as a symbol to wish for the growth and prosperity of their families. In ancient times, herrings were called kado in Japanese, which became kazunoko over time.

Top right: Tazukuri

One of the most representative osechi dishes. Tazukuri means dried baby sardines, or sometimes it is prepared by searing baby sardines and simmering them in a thickened sauce made with soy sauce, sugar and rice wine called mirin. In earlier days, baby sardines mixed with ash was used as field fertilizer, so the baby sardines became a food that symbolized the wish for an ample harvest, especially for the Five Grains.

Center left: Kuri kinton (sweet mashed chestnuts)

Chestnuts are one of the most abundant foods from the mountains all over Japan. Dried, ground chestnuts are called kachiguri. As kachi sounds like “triumph” in Japanese, mashed chestnuts were eaten before soldiers went to war.

Meanwhile, kinton is a type of sweet influenced by China. The two(chestnuts and kinton) were combined and their golden color symbolizes affluence, the kuri kinton became a regular food in osechi, entailing the wish for good business.

Center: Prawns

Prawns have long antennas and are a symbol of longevity, evoking an image of an old man with a bent back. It is used in osechi cuisine to wish for the family’s longevity.

Center right: Black beans

Since ancient times, the color of black was believed to have the power to repel evil. Black beans are called kuro mame in Japanese. Kuro has the same sound in Japanese as “hardship” and mame sounds the same as “diligent.” As such, people ate black beans as a way to wish for diligence in their work, robust health and to live life without illness or bad luck.

In the Kansai region of central Japan, black beans are supposed to be cooked without causing any wrinkles, whereas in Kanto they are supposed to have wrinkles. Either way, black beans, with or without wrinkles (a sign of old age), are eaten as a food to wish for health and longevity.

Bottom left: Kombu kelp roll

Kombu kelp sounds similar to yorokobu (to delight in) and as such, is used extensively as a good luck food. They are either tied into a ribbon shape and cooked or rolled up with fish in the middle. In some regions, people insert pieces of kombu kelp into their New Year’s straw festoons.

Bottom center: Red and white kamaboko (fish paste)

Red and white are the colors of offerings to gods, and people used to offer white rice and rice dyed red. Red symbolizes protection from evil, and white represents holiness. There is also a rule to put the red (or more vividly colored) item on the right and white item on the left.

Bottom right: Kohaku namasu (red and white vegetables)

Namasu (carrots and daikon radish) are arranged like mizuhiki, festive Japanese red and white paper strips. It is a regular dish for all festive occasions and is the best-known vinegared dish in Japan. In some regions, people also add fresh fish to the namasu. Just like the red and white kamaboko, the red and white colors symbolize offerings to gods.

When we know the origin of each item in osechi cuisine, their flavors can become deeper. Why not spend the New Year with your family, surrounding a table full of osechi dishes and sharing the happiness for a good start to the year?

Writer : HISAYO IWABUCHI / Photographer : YUTA SUZUKI

*Some of the images posted on our website have been provided by those whom we interviewed.

Source: What is Japanese cuisine?—The origins and development of Japanese dietary culture, Ayao Okumura, published by Nobunkyo

Address: Ajinomoto Group Takanawa Research Center 3-13-65 Takanawa, Minato-ku, Tokyo

Hours: 10:00am~5:00pm

Open: Monday - Saturday

Closed Sunday and public holidays (including New Year)

Website (Japanese only): http://www.syokubunka.or.jp

*Unscheduled closures can occur. To avoid disappointment, check website before visiting.

About SHUN GATE

Shun is the Japanese word which refers to the period of time in which raw ingredients are in season. As such, SHUN GATE is the gate to the stories of the people, techniques, technologies, and the lands that make up Japanese food culture and its seasonal characteristics.

Originally published December 2016

The main food associated with Japan’s New Year is none other than osechi cuisine.

The number of stacked boxes the food comes in, how it is presented and what items it comprises of may have changed with time, but the image of a Japanese family surrounding a table full of osechi, wishing for happiness in the coming year, has not.

To understand more about Japan’s New Year cuisine, we visited Takako Tsubuku, Managing Director of the Ajinomoto Foundation for Dietary Culture, a public interest incorporated foundation.

The surprising origin of osechi, born from the Japanese New Year

From the large volumes of books housed in the Ajinomoto Foundation for Dietary Culture, Tsubuku showed us a book by Ayao Okumura, a leading researcher of Japan’s traditional cuisine, titled What is Japanese cuisine?

Takako Tsubuku, Managing Director of the Ajinomoto Foundation for Dietary Culture

Tsubuku says that this book mentions the surprising origin of osechi, which Okumura figured out from his research on ancient manuscripts.

According to Okumura, the main dish eaten during Japan’s New Year used to be zoni, which is cooked rice cakes in soup with vegetables; osechi was originally a simple assortment of several dishes that accompanied the zoni, which was the main dish.

Like obon in mid-August, Japanese people used to believe that their deceased ancestors came back to their homes in the New Year as well, this time as “gods of the year.” Families shared the rice cakes and vegetables that were offered to the gods in the New Year, which marked the beginning of zoni. As time passed and a larger variety of ingredients became available, people from samurai and rich merchant households started to prepare food in large stacked boxes.

Also, the custom of cooking food on New Year’s Eve, saving it for the New Year, takes after the Chinese Cold Food Festival, which takes place around the New Year. In China, people avoided lighting a fire in their furnaces during the New Year because Taoism taught them that the god of furnaces visited them in the New Year.

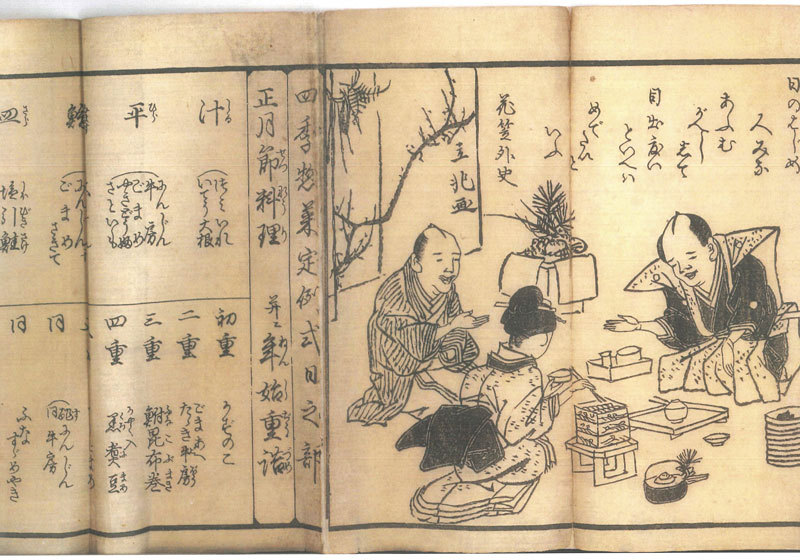

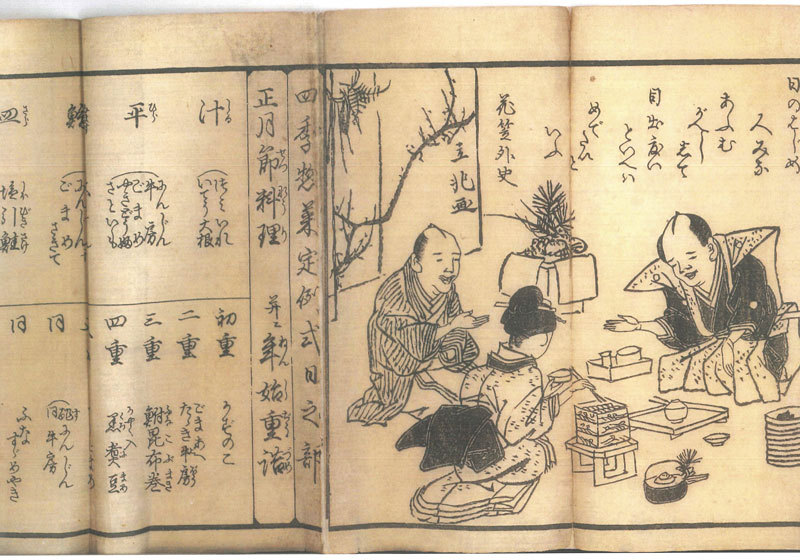

Source: "Banka Nichiyou Souzai Manaita" (Owned by Ayao Okumura)

* Published in "What is Japanese Cuisine?" by Ayao Okumura

* Published in "What is Japanese Cuisine?" by Ayao Okumura

In Japan, it is said that people also started cooking food for the three first days of the year on New Year’s Eve and put the food in stacked boxes, to avoid tainting the “holy fire” needed to cook the zoni shared by the gods and people over the New Year.

As such, osechi started to spread among the people from around 1700 as a cuisine to welcome the gods in the New Year.

The word osechi is also said to have come from sechie, seasonal feasts held in the New Year and other festive seasons that the emperor and his vassals would have. This tradition started in the Nara period (710 to 764). The book states that in the late Edo period (1603 to 1868), people started calling the New Year feast osechi.

Osechi, the cuisine that changes with time

After the Meiji period (1868 to 1912), the dietary lifestyle of Japanese people changed significantly and they started to use chicken broth and meat when making zoni. Similarly, items served in stacked boxes became more luxurious and osechi began to secure its place as the main food of the Japanese New Year (at this stage, the cuisine itself was not called osechi yet).

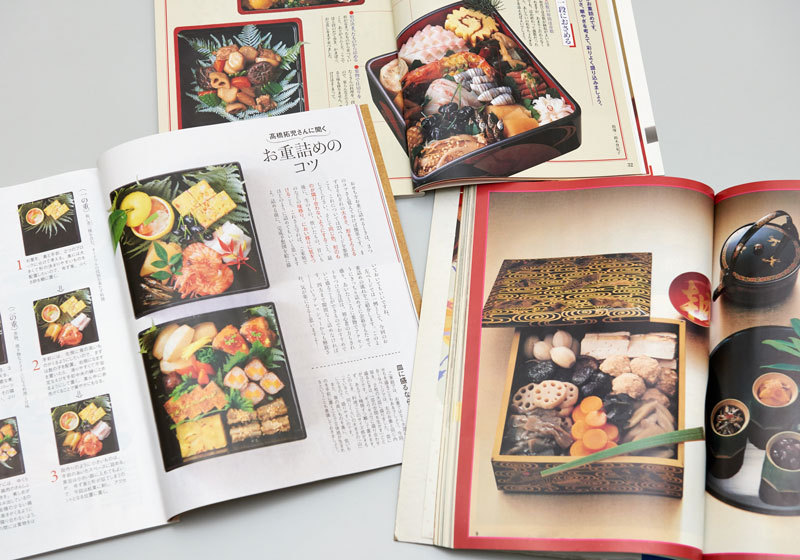

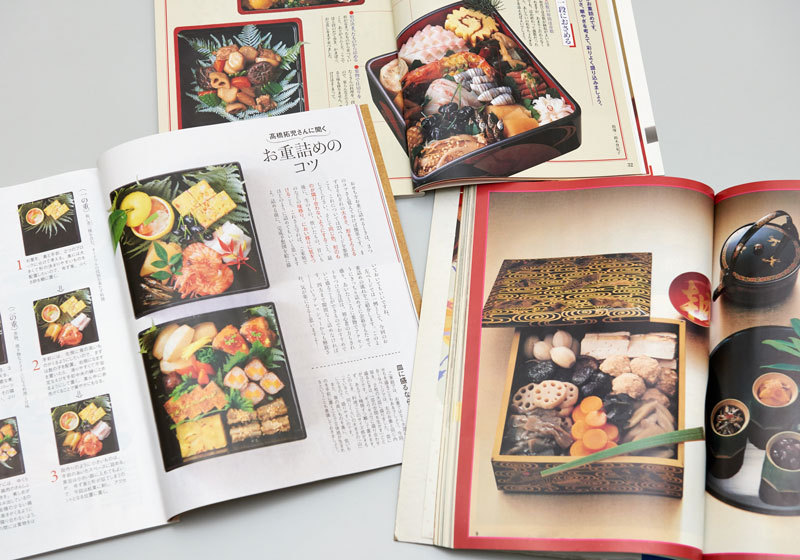

“Friends of Cooking” 1st issue, volume 8 (January 1920)

The menu of a cooking class held by a Kappo (traditional Japanese) cuisine chef in the Taisho period (1912 to 1926) Tokyo shows datemaki (egg rolls), kamaboko (fish cake) and kinton (mashed chestnuts) for the first time in recorded media. There are also records that the Osaka Mitsukoshi Department Store sold sets of filled osechi boxes. Later in the Showa period (1926 to 1989), ham and roast beef made their way into the menu, creating eclectic Japanese-Western style stacked boxes.

“Friends of Cooking” 1st issue, volume 18 (January 1930)

“The Ajinomoto Foundation for Dietary Culture has back issues of the cooking magazine ‘NHK Kyouno Ryouri (Cooking Today)’. If you look at the New Year’s issues from ten, twenty years ago, you can see that osechi has changed from generation to generation—going through them is fun. You can see that they were influenced by Western hors d’oeuvres, too. There has been a growing emphasis on beautiful color coordination. Osechi will probably continue to evolve,” says Tsubuku.

Osechi changes with time. But the practice of families’ wishing for each others’ happiness and eating lucky foods at the beginning of the year, the heart of this cuisine, will probably never change.

Enclosing the wish for unchanging happiness

What does each food item in osechi cuisine symbolize? We asked Tsubuku to explain the nine representative osechi foods.

Top left:: Pounded burdock root

Burdock roots are cooked until soft, pounded and then slit open. In some areas it was called “open burdock” and was thought to be a dish that would “open up” good luck. Burdock root was also believed to remove “bad” blood and had been a good luck food long before it became a member of osechi cuisine. Also, as burdock grows long, fine roots in the ground, it also entails the wish for the household to remain safe and prosperous.

Top center: Kazunoko

Kazunoko is herring roe. Herring is called nishin in Japanese, and is also a homophone for “two parents.” As such, people use kazunoko as a symbol to wish for the growth and prosperity of their families. In ancient times, herrings were called kado in Japanese, which became kazunoko over time.

Top right: Tazukuri

One of the most representative osechi dishes. Tazukuri means dried baby sardines, or sometimes it is prepared by searing baby sardines and simmering them in a thickened sauce made with soy sauce, sugar and rice wine called mirin. In earlier days, baby sardines mixed with ash was used as field fertilizer, so the baby sardines became a food that symbolized the wish for an ample harvest, especially for the Five Grains.

Center left: Kuri kinton (sweet mashed chestnuts)

Chestnuts are one of the most abundant foods from the mountains all over Japan. Dried, ground chestnuts are called kachiguri. As kachi sounds like “triumph” in Japanese, mashed chestnuts were eaten before soldiers went to war.

Meanwhile, kinton is a type of sweet influenced by China. The two(chestnuts and kinton) were combined and their golden color symbolizes affluence, the kuri kinton became a regular food in osechi, entailing the wish for good business.

Center: Prawns

Prawns have long antennas and are a symbol of longevity, evoking an image of an old man with a bent back. It is used in osechi cuisine to wish for the family’s longevity.

Center right: Black beans

Since ancient times, the color of black was believed to have the power to repel evil. Black beans are called kuro mame in Japanese. Kuro has the same sound in Japanese as “hardship” and mame sounds the same as “diligent.” As such, people ate black beans as a way to wish for diligence in their work, robust health and to live life without illness or bad luck.

In the Kansai region of central Japan, black beans are supposed to be cooked without causing any wrinkles, whereas in Kanto they are supposed to have wrinkles. Either way, black beans, with or without wrinkles (a sign of old age), are eaten as a food to wish for health and longevity.

Bottom left: Kombu kelp roll

Kombu kelp sounds similar to yorokobu (to delight in) and as such, is used extensively as a good luck food. They are either tied into a ribbon shape and cooked or rolled up with fish in the middle. In some regions, people insert pieces of kombu kelp into their New Year’s straw festoons.

Bottom center: Red and white kamaboko (fish paste)

Red and white are the colors of offerings to gods, and people used to offer white rice and rice dyed red. Red symbolizes protection from evil, and white represents holiness. There is also a rule to put the red (or more vividly colored) item on the right and white item on the left.

Bottom right: Kohaku namasu (red and white vegetables)

Namasu (carrots and daikon radish) are arranged like mizuhiki, festive Japanese red and white paper strips. It is a regular dish for all festive occasions and is the best-known vinegared dish in Japan. In some regions, people also add fresh fish to the namasu. Just like the red and white kamaboko, the red and white colors symbolize offerings to gods.

When we know the origin of each item in osechi cuisine, their flavors can become deeper. Why not spend the New Year with your family, surrounding a table full of osechi dishes and sharing the happiness for a good start to the year?

Writer : HISAYO IWABUCHI / Photographer : YUTA SUZUKI

*Some of the images posted on our website have been provided by those whom we interviewed.

Source: What is Japanese cuisine?—The origins and development of Japanese dietary culture, Ayao Okumura, published by Nobunkyo

Information

Ajinomoto Foundation for Dietary CultureAddress: Ajinomoto Group Takanawa Research Center 3-13-65 Takanawa, Minato-ku, Tokyo

Hours: 10:00am~5:00pm

Open: Monday - Saturday

Closed Sunday and public holidays (including New Year)

Website (Japanese only): http://www.syokubunka.or.jp

*Unscheduled closures can occur. To avoid disappointment, check website before visiting.

About SHUN GATE

Shun is the Japanese word which refers to the period of time in which raw ingredients are in season. As such, SHUN GATE is the gate to the stories of the people, techniques, technologies, and the lands that make up Japanese food culture and its seasonal characteristics.

Liked this story? Like DiGJAPAN!

on Facebook for daily updates!

THIS ARTICLE IS BASED ON INFORMATION FROM 02 10,2017 Author:SHUN GATE

NEW COMMENT | 0 COMMENTS

Open a DiGJAPAN!

account to comment.

Open a DiGJAPAN! Account